Consider this future scenario:

Home insurance firms now mandate installation of smart smoke alarms. One popular low-cost alarm has developed a speaker hardware fault and recently stopped providing software security updates after just 2 years. Adam, who can financially afford to, simply buys another alarm and throws the broken one away. Ben however, cannot afford a new alarm and faces unexpected financial consequences. The lack of security means his home network has been compromised and hackers intercepted his banking log-in credentials. Worse still, the faulty alarm did not warn him of a small housefire in the night, causing damage he cannot afford to repair. The insurance company is refusing to pay the claim, as unknown to Ben, they recently removed the device from their list of accredited alarms.

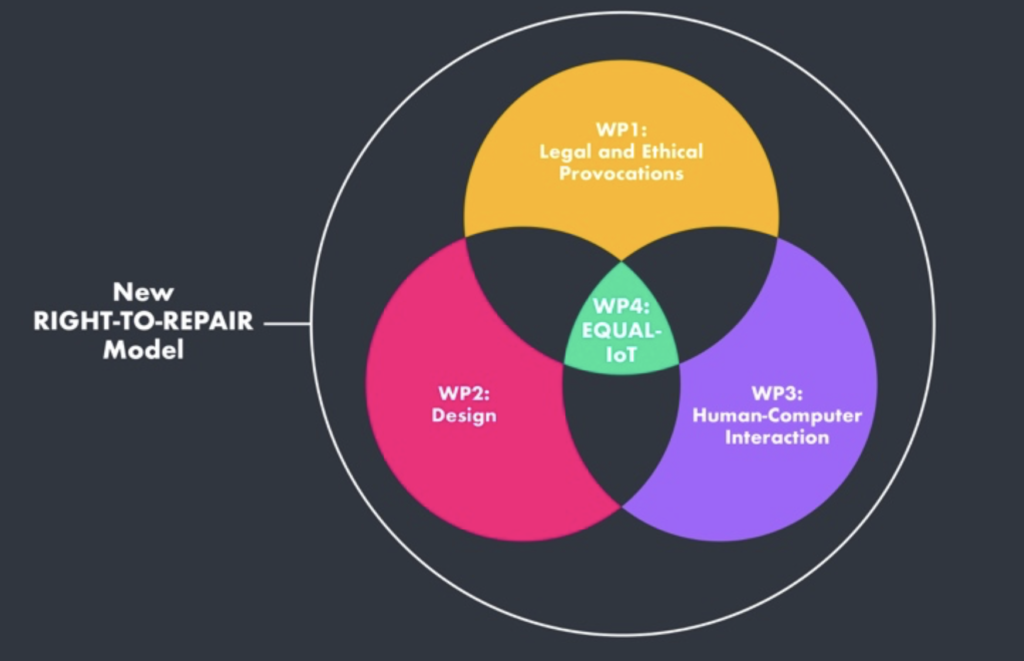

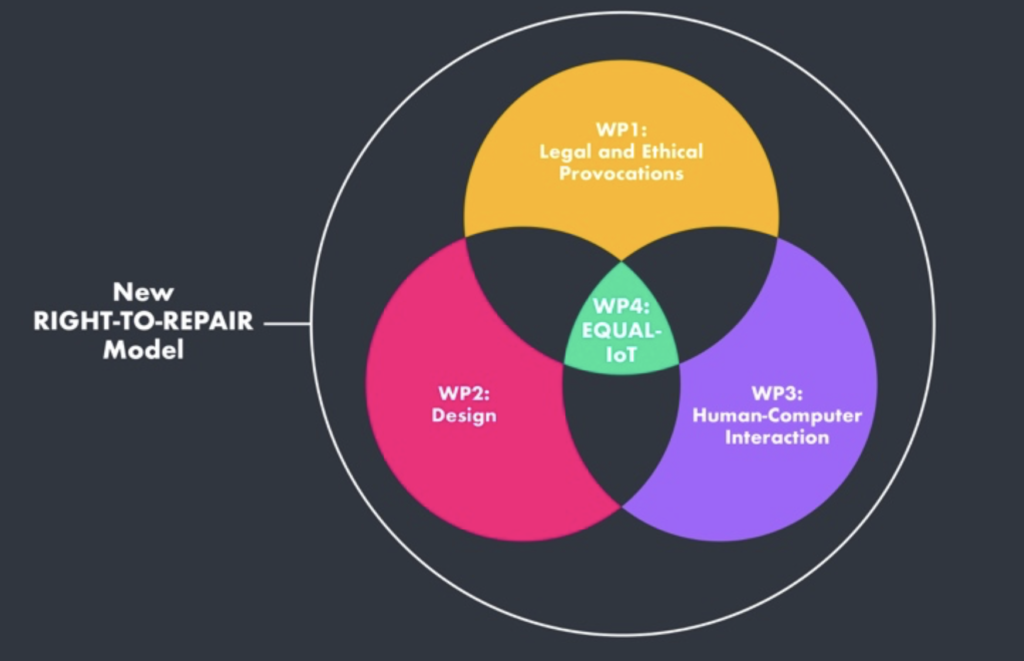

October 2022 is the start of Fixing The Future: The Right to Repair and Equal-IoT – a £1.2m EPSRC project that examines how to avoid such future inequalities due to the poor long-term cybersecurity, exploitative use of data and lacking environmental sustainability that defines the current IoT. Presently, when IoT devices are physically damaged, malfunction or cease to be supported, they no longer operate reliably. Devices also have planned obsolescence, featuring inadequate planning for responsible management throughout their lifespan. This impacts on those who lack the socio-economic means to repair or maintain their IoT devices, leaving them excluded from digital life for example, with broken phone screens or cameras.

This project is an ambitious endeavour that aims to develop a digitally inclusive and more sustainable Equal-IoT toolkit by working across disciplines such as law and ethics, Human Computer Interaction, Design and technology.

Law and Ethics: To what extent do current legal and ethical frameworks act as barriers to equity in the digital economy, and how should they be improved in the future to support our vision of Equal-IoT? We will examine how cybersecurity laws on ‘security by design’ shape design e.g. the proposed UK Product Security & Telecoms Infrastructure Bill; how consumer protection laws can protect users from loss of service and data when IoT devices no longer work e.g. the US FTC Investigation of Revolv smart hubs which disconnected/bricked customer devices due to a buy-out by Nest.

Design: How can grassroots community repair groups help inform next-generation human-centred design principles to support the emergence of Equal-IoT? We will use The Repair Shop 2049 as a prototyping platform to explore the legal and HCI related insights in close partnership with The Making Rooms (TMR), a community led fabrication lab working as a grassroots repair network in Blackburn. This will combine the expertise of local makers, citizens, civic leaders and technologists to understand how best to design and implement human-centred Equal-IoT infrastructures and explore the lived experience of socio-economic deprivation and digital exclusion in Blackburn.

Human Computer (Data) Interaction (HDI): How can HCI help operationalise repairability and enable creation of Equal-IoT? We will create prototype future user experiences and technical design architectures that showcase best practice on how Equal-IoT can be built to be more repairable and address inequalities posed by current IoT design. Our series of blueprints, patterns and frameworks will align needs of citizens technical requirements and reflect both constraints and opportunities manufacturers face.

Image created and provided by Michael Stead

This is an exciting collaboration between the Universities of Nottingham, Edinburgh, Lancaster and Napier, along with industry partners –Which?, NCC Group, Canadian Government, BBC R&D, The Making Rooms.

For more information about this project, contact Horizon Transitional Assistant Professor Neelima Sailaja